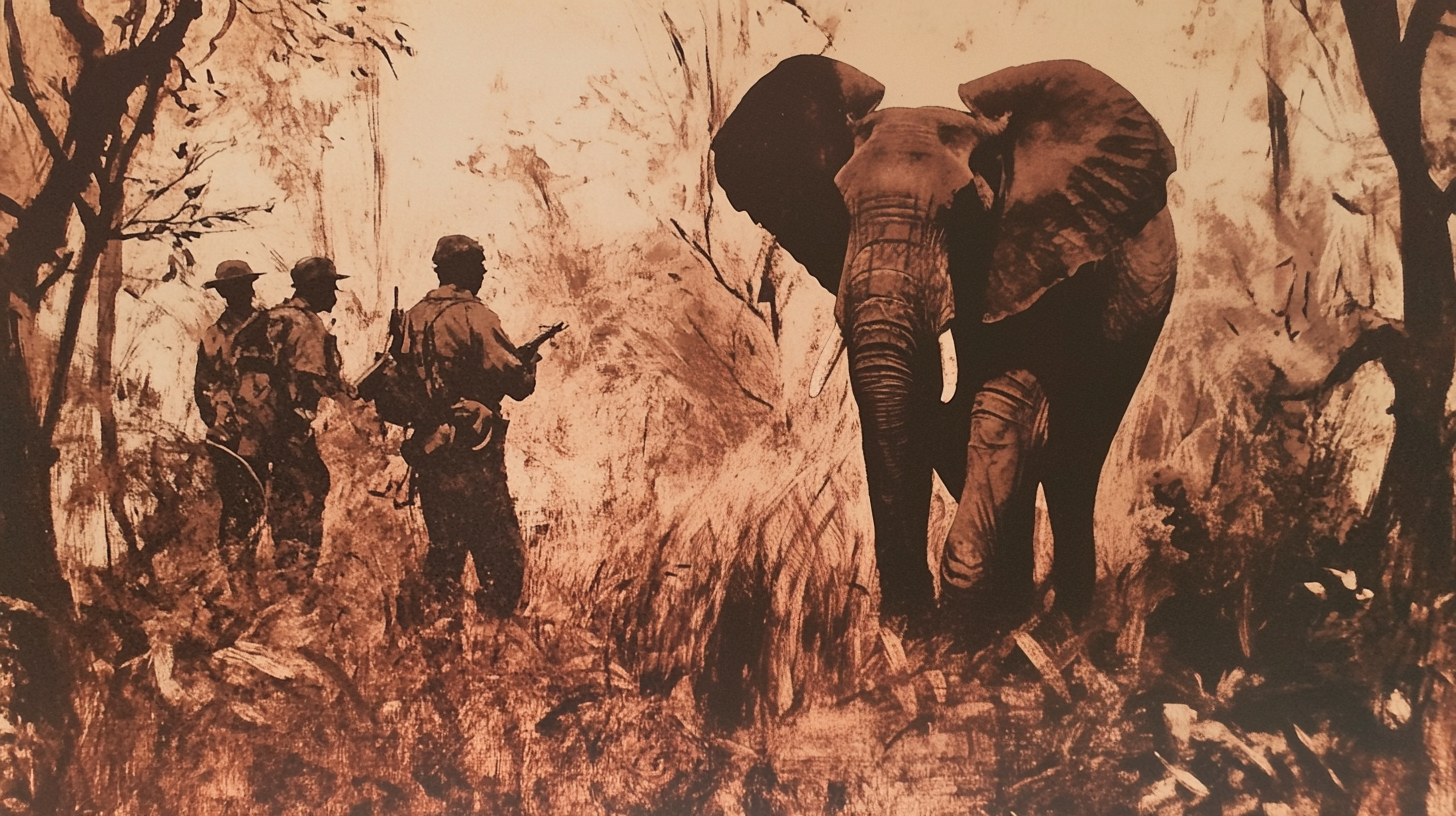

What Did the Elephants Ever Do to You, Allan?

A tragicomic lesson in ecological misjudgment, overconfident experts, and the eternal human hunger for simple explanations.

Just because something sounds right, doesn’t mean that it is right.

In the 1950s, a Zimbabwean biologist named Allan Savory had a problem: desertification. The African grasslands were collapsing under what he and his colleagues believed was the strain of too many elephants. The logic was simple: more elephants = less vegetation, therefore they must be eating it all.

So they did what experts do. They made a plan.

Savory lobbied to have the elephant population culled in massive numbers. Over the course of a few years, more than 40,000 elephants were killed by government decree.

And the desertification got worse.

It turns out the elephants weren’t the problem. They were part of the solution. Their toenails tilled the earth. Their movements spread seeds. Their migration patterns prevented overgrazing. By removing them, Savory had accidentally accelerated the very thing he was trying to stop.

He would later call it the greatest blunder of his life.

I think about this story a lot.

Because this is what it looks like when an expert - acting on incomplete models, pressured by urgency, and backed by institutional credibility - takes action before they understand the system they’re altering.

It’s not just a fable about ecosystems. It’s a mirror for every field I’ve ever worked in: software, consulting, AI, M&A, marketing.

We love scapegoats. Especially elegant, legible ones. Something we can point to and say: “There. That’s the problem. That’s what needs to go.”

And then we pull the trigger.

But systems are not machines. They’re not spreadsheets or levers or knobs. They’re living, interdependent, nonlinear feedback loops. And once you intervene, you own the consequences - seen or unseen.

Savory was not evil. He was not stupid. He was just certain.

And certainty, untethered from humility, is what destroys life.

What are we culling today?

What vital, misunderstood players have we labeled as inefficiencies, distractions, or blockers?

• Is it the “underperforming” employee who’s actually holding the culture together?

• Is it the slow onboarding process that’s quietly preventing downstream chaos?

• Is it the boring legacy software that holds critical tribal knowledge no one’s documented?

• Is it the grumpy team member who keeps raising the same inconvenient truth?

In the rush to optimize, do we even stop to ask what function the elephant was serving before we shoot it?

Experts love to sell us the illusion of control.

And we’re hopelessly addicted to the self-indulgent notion of certitude. Especially when it comes packaged in a well-formatted PowerPoint.

But real wisdom lives elsewhere.

It lives in pattern recognition. In slow questions. In the willingness to say: I don’t know yet.

We don’t need fewer elephants. We need fewer people who think they know what elephants are for.

So next time someone tells you the solution is obvious - look for the elephant in the background. And ask what it might be doing that they haven’t considered.

It might just be holding the ecosystem together.